E-learning experiences in the NETIS project

Elearning experiences in the NETIS project

Author(s):

Dr István Bessenyei, University of West Hungary, istvanbess@yahoo.de Zsolt Tóth, University of West Hungary, zstoth75@gmail.com

Sopron, 2007 autumn

Publication of this report is supported by:

|

|

This project has been funded with support from the European Commission. This publication reflects the views only of the authors, and the Commission cannot be held responsible for any use that may be made of the information contained therein

[header=Introduction]

Introduction

In the first half of the academic year of 2007/2008 we tested the NETIS project teaching material on a group of 14 students of the faculty of Economics in the University of West Hungary (NyugatMagyarországi Egyetem). Instruction was delivered in the form of blended learning. The two lessons of instruction per week were held in the wellequipped IT laboratory. The students worked within the Moodle learning management system. We selected four out of 13 chapters of the teaching material as we decided that more than this in a period of half a semester would be too much to handle. (The selected themes were technology, networks, eadministration, elearning).

What were the main objectives of the experiment?

• Organising learning into a network, i.e. students studying from each other.

• The creation of an eportfolio and knowledge map which would enable us to mutually exploit one another’s tacit and explicit knowledge.

• Testing creative project tasks with Internet support.

The article summarizes the theoretical presuppositions of the experiment, the tools employed and the difficulties that came up during its implementation.

[header=Networks, communication overload and knowledge map]

Networks, communication overload and knowledge map

A characteristic feature of traditional teaching in industrial societies is the hierarchical distribution of knowledge. The model form of this is the noninteractive conventional lecture with a top to bottom transmission of information. In the framework of traditional seminars discussion and communication takes place within a restricted temporal and spatial framework. The limited circulation of printed books make it necessary for professors to hold a lecture based on their own course books (or to imply read them out) and the students try to note down what they hear just as students did in the Middle Ages. In the framework of traditional seminars discussion and communication takes place within a restricted temporal and spatial framework.

The new communicational tools expand these limitations. Technology in the information society enables the organisation of persons, knowledge warehouses and institutions into networks. With the help of Web2based technology the teacher and students are able to keep in constant contact with each other with no temporal or spatial hindrance. The teacher can be reached anywhere by electronic mail. The teaching material (and even teachers’ lectures) can be accessed and commented on from any Internet workstation in the world – as can the students’ work posted on the Internet. The students can independently upload the knowledge material and can easily store their tasks and comments in a learning environment.

However, this opportunity also gives rise to new problems. One of these is information overload. In network learning essays, exercises and requests for support can be forwarded quickly and efficiently by electronic mail. However, if the teacher remains the only source of knowledge and the only tutor, sooner or later he/she will be lost amidst the overwhelming amount of electronically stored texts, exercises and messages.

Thus, a contradiction arises, namely that if network education is used in the traditional system of centralised knowledge distribution with every student turning to the teacher with their questions and everything else, and the teacher checking every step of the knowledge acquisition process, this will in the short term lead to an unmanageable overload of information.

The methods of traditionally centralised knowledge distribution and the opportunities afforded by the network are thus difficult to reconcile. The network virtually forces learning from one another, i.e. decentralised knowledge distribution. In this system students have to learn from each other and ask for help from other tutors. Following this path frees the teacher from information overload. However, this method is only possible if we know what kind of experience, knowledge and competence the other network partners have, since armed with such facts we can decide whom to turn to with what questions. This can be facilitated by the exploration, storage and presentation of personal knowledge, which necessitates the creation of personal eportfolios and knowledge maps.

Hence, a whole new series of questions arose:

• Do the students have the knowledge (informal, tacit, experiential) that fits in with the themes of the course?

• Do the students need to adjust to the course or does the course have to be adjusted to their preliminary knowledge?

• How can students learn from one another (and indeed how can they be taught), if personal knowledge is not represented? Does the present organisational framework have the potential for such intensive work to be done so that individual competenceportfolios and knowledge maps enabling students to use each other as sources of knowledge could be created?

• How is it possible to create the opportunity for the teachers and students of other traditional universities to be integrated into the cooperative knowledge production afforded by network learning?

• How does the role of the teacher change in such an operational method?

• Is this teaching method suitable for preparing students to meet the rigidly designed exam requirements?

• Is the Hungarian university system of today ready to embrace this kind of an intensive tuition tailored to the individual?

• What does the “knowledge” which must be transferred actually mean?

• While teaching methods are closely tied to the curricula, the present curricula do not support experimental projects. How can this contradiction be resolved?

[header=Didactic experiences of network learning]

Didactic experiences of network learning

If we take cooperative, network learning seriously and also take it seriously that students use each other as a source of information (and we involve the experts of other universities in tutoring), a professional competenceportfolio system facilitating welldocumented and generally accessible sources of information needs to be set up. This necessitates a wellconstructed internal knowledgemanagement base and that other universities be part of the knowledge network (in a technical sense too). Such logistics require that every participant has an individual (professional) knowledge map and competenceportfolio.

Again, several questions arise:

• What should be included in the knowledge maps?

• How can knowledge intended to be used by others be understood and recorded?

• How should we go about selfexploration through which tacit knowledge and informal experiences acquired in everyday life, can come to the surface and be made explicit?

• How can we articulate this and give it form?

With the help of narrative knowledge management it is possible to reveal the tacit knowledge of individuals and organisations through an analysis of narratives. The students’ introduction of themselves were the first such narratives. A whole storehouse of life experience was revealed during these narratives. The success stories built into these narratives provided help in formulating the speaker’s tacit, experiential knowledge.1

The function of the databasemanagement function (WIKI) built into Moodle provided help in the preparation of an eportfolio, for which the following short list of possible themes was proposed:

• Learning biography;

• learning style;

• completed tests, exercises;

• selected sources of study;

• hobbies;

• success stories;

• family background;

• participation in real and virtual social networks;

• work experience;

• experience abroad;

• knowledge map.

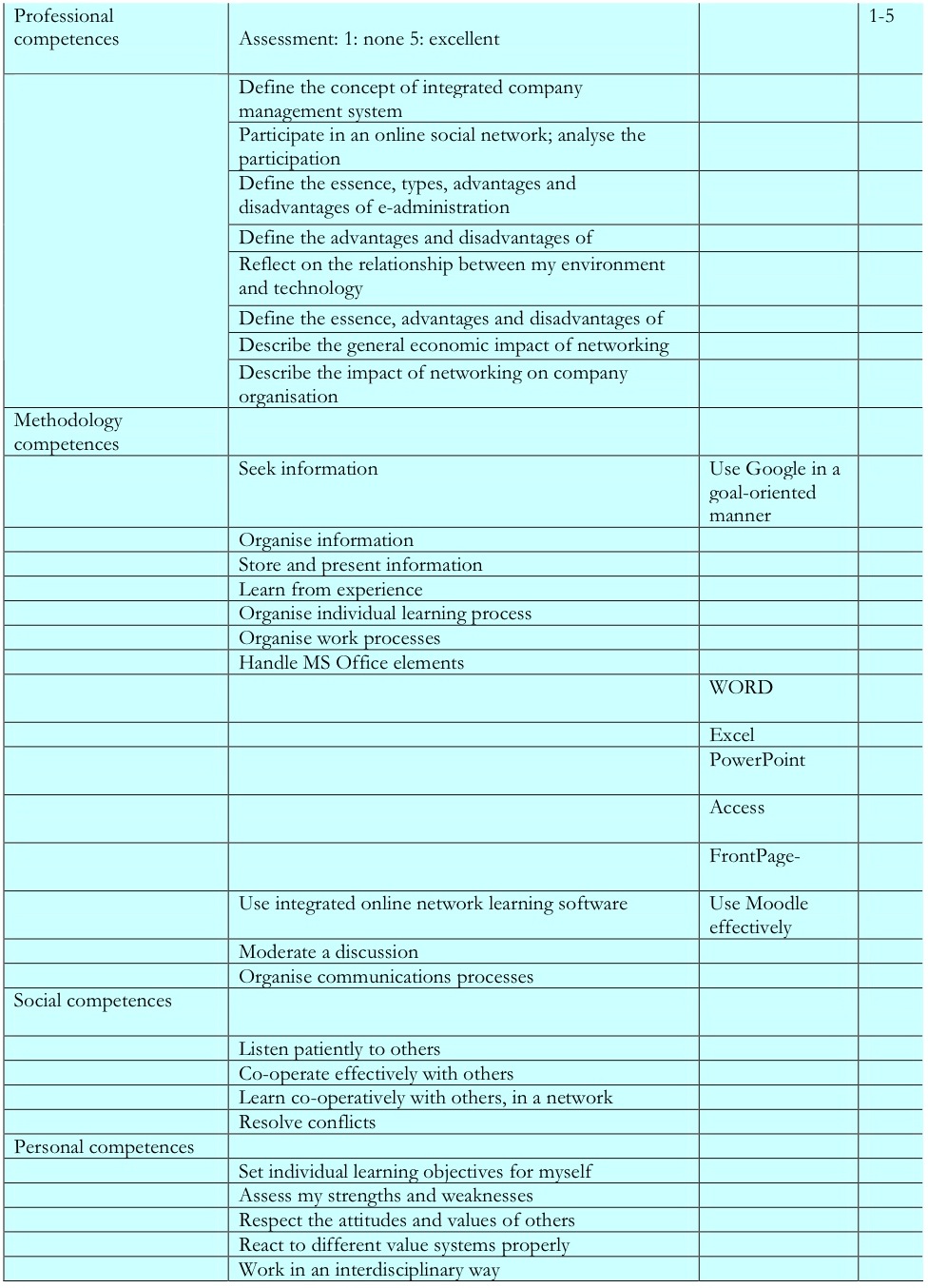

The competenceportfolio table planned through joint work served the goal of guiding students in the preparation of their own individual knowledge map, thus providing a source of knowledge, which is more system

1 “The narrative is a central mechanism that mediates social knowledge. The narrative forms a bridge between tacit and explicit knowledge. It renders the expression of social knowledge possible as well as its use in learning without the constraint of preliminary assessment. Institutions are most effectively able to preserve their respective stories if they provide the opportunity for these to be published. Archiving systems similar to databases, digital teaching sytems and videocams are more effective if they facililitate the recording and description of narratives.” (Linde, 2001)

atical and easier to document than biographical narratives. The following table contains an auxiliary tool referred to above.

1st Table: Competence catalogue We supplied the particular competencerequirements (learning objectives) of the chapters in a separate list. The students were able to give marks for each item of the competencelist at the beginning and end of the course, which allowed them to follow the development of their knowledge.

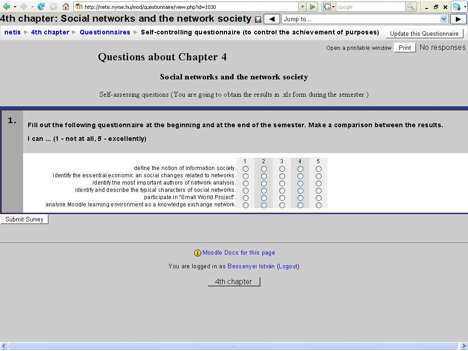

The first figure shows the selfassessment system of Moodle.

1st Figure: The selfassessment questionnaire illustrated by an example from the chapter entitled Network

|

Chapter 4: Social networks, network society NETISnetworksquestionnairesselfassessment (to assess the acquisition of objectives) Question in connection with the chapter “Network” Selfassessment questions (The results will also be sent to you in an Excel file during the semester.) Complete the questionnaire at the beginning and end of the semester. Compare the results. I am able to … (1: not at all, 5: excellently)

• define the notion of network society.

• identify the essential economic and social changes relating to networks.

• identify the most important authors of network analysis.

• identify, describe the characteristics of the social network used.

• participate in the “Small World Project”.

• analyse the Moodle learning environment as a knowledgeexchange network.

[header="Creative projects"]

“Creative projects”

In every instance Internet supported tasks were assigned to the competences that were to be mastered. We designed these projecttype tasks in such a way that their completion would lead to the acquisition of the desired competence. In theory, the students were able to select those tasks to complete which (revealed with the help of the competence catalogue) could compensate for their gaps in knowledge. All of these elements of the integrated learning environment (competence catalogue, project ideas, information, opportunities for selfevaluation and communication) enable participants to develop that particular competence that they were the most motivated to achieve based on their personal drive. Toolbars containing checklists, tables, flowcharts and methodology guides, as well as accessible lists of online and printed literature were provided for the projects.

Exploiting the opportunities provided by the Internet and Moodle, we organised search, knowledge management and database development projects. The chapters contain selffillin multiple choice test questions and traditional revision questions.

Which were the typical tasks and creative projects of the course that could be used for every chapter? 2

1. Glossary development

The students look into whether there are expressions in the text of the chapter which they cannot understand. These are placed in the glossary (lexicon) of the given chapter. If they are not able to find a suitable definition, they then use the Internet to find explanations that help them to understand the expression. These are stored in the glossary of each chapter. Thus, by the end of the semester a glossary is developed through collective work, which helps with individual problems of understanding.

2. Analysis of Internet forums

The students select an Internet forum suitable for the topics of the chapter and analyse it in regard to what kind of information exchange is taking place in them. Possible questions:

• Information flow (centralised vs. decentralised diffusion of information).

• Content of information (alternatively: their position on the data, information, knowledge/master knowledge scale – relative to the level of the question posed).

• The degree of informationspread/proliferation spontaneity/organisation.

• The relevance of the information to the set objective.

• The degree to which the credibility of the information can be validated.

2 Every chapter also contained chapterspecific tasks.

The students organise a type of information exchange forum in which their own collection of links, parts of texts and book titles connected to the chapter can be stored, and these can be exchanged and commented on by them. They organise debates on the Internet forum on selected problems from the chapter.

3. Eportfolio

The students make their own eportfolios with the assistance of Moodle’s WIKI function. The eportfolio facilitates network, cooperative learning. One of the important points when creating the eportfolio must be that when a given piece of information is provided it must help the other participants of the network to understand the tacit knowledge and knowledge source the portfolio’s maker offers.

4. Learning diary (blog)

The students can comment on their own learning experiences in Moodle’s blog. The suggestions, ideas and difficulties they express provide help in the ongoing development of the course.

5. Essay on personal experiences

In an essay (a short, informal study, a report on events, or a diary) the students describe their personal experiences of the changes brought about by the information society.

[header=The issue of assessment]

The issue of assessment

It is well known that traditional exams assess knowledge and its uniform presence but they also serve as a differentiating variable when distributing rewards (scholarship, accommodation in dormitories, medals of distinction, jobs).

In traditional learning the input (learning time and learning algorithm) is uniform, while the output (the examination results achieved) differs as it is dependent upon individual performance. If output regulation is applied, learning routes, algorhythms and learning time differ according to the individual, but – in an ideal situation – output is uniform or at least approaches being uniform. Thus, the traditional examination as a tool for assessment is theoretically not even necessary because in the case of network, selforganised learning it is of much greater importance to ensure that variable learning routes and flexible time frames are provided and that all the conditions for selforganised study are available. The technical background for selforganised learning was provided. However, the assessment procedures of our course were at sharp variance with today’s organisation of learning at universities, which requires formal and uniform assessment that can be expressed in marks.

Due to its nature, assessment in the form of short texts about each student’s work would have been best suited to our course. However, the marks had to be entered into the lecture books. In the end, the work done in the semester was evaluated on the basis of the level of the students’ participation in collective work, the main elements of which were the following:

• making one’s own knowledge map;

• completing a set number of tasks in the integrated course management programme;

• keeping a search log;

• participation in compiling the lexicon containing the subject’s basic terms

• writing an essay

The average of the individually evaluated five types of tasks was the actual mark entered into the students’ lecture books.

[header=Contradictions, obstacles]

Contradictions, obstacles

1. Knowledge maps and individual learning routes

What difficulties were encountered when using the knowledge map? Drawing up the knowledge map entailed collaborative elements built on using each other’s experiences but it did not serve as a genuinely mutual and professional knowledge base. Since the exploration of tacit knowledge, the recognition of everyday experiences as knowledge, and the analytical definition of knowledge levels were very time consuming, there was not enough time and energy left to motivate and organise a real exchange. The economics students who were inexperienced in the types of tasks the elearning course expected them to perform, for example in rendering their everyday and “tacit” i.e. nonstructured – knowledge explicit and explaining this. The formulation of experiential knowledge in the form of organised concepts proved difficult and required the use of special methodology.

Although we had some creative tasks that included elements such as learning from each other, the practical use of the competencecatalogues, and the application of these were rather ad hoc and rare. For example, it was not possible to motivate the students to comment on one another’s solutions to tasks. (However, students who were more experienced in searching the Internet and using Moodle successfully helped the beginners and it all developed in a spontaneous way.)

Another plan that proved to be an illusion was that the students would follow individual learning routes based on their individual knowledge maps. Although the students did fill in the selfassessment tests, we did not use the results of these to explore ramified learning routes with several stages. A completely different kind of logistics and a different organisational form would have been necessary for this, which could not be realised within the framework of our project. The study of individual knowledge maps and the organisation of each student’s learning route could not be carried out in just one semester.

2. The regulatory system

Institutional regulatory systems are generally slow to follow changes. Hyperlearning cannot be squeezed into the traditional temporal, spatial and legal frameworks of linear education. In network teaching the contents and methods must be adjusted to the prior represented knowledge and it must make individual learning routes possible. The traditional regulatory prescriptions for classroom teaching are not suitable for this since different didactics and working methods are needed for elearning. This represents a continuous obstacle and source of conflict.

On the other hand, switching over to elearning is an innovation that in the short term requires a big investment both intellectually and materially: new professional competences are needed, and the compilation of a curriculum system, its testing and the training of teachers require a great deal of time and money. Furthermore, the workload for teachers may increase significantly. Put somewhat simply: in the first phase of introducing elearning teachers would have to work three times as much for the same salary.

3. Theory vs. Practice

On a theoretical level elearning has been splendidly engineered. Almost everything has been written about it that can possibly be said at the level of theoretical abstractions and didactic speculations. Countless analyses exploring the potential organisational and didactic consequences as well as the (mostly enthusiastic and optimistic) prospects of elearning have been written. Yet, we are really just making the first steps in the innovative institutionalisation and practical testing of elearning. So far there is little useful practice that is built on consistent didactic principles, and feedback on concrete experiences is lacking. Because of this we were only able to rely on the few reports specifically written about Hungarian projects.

4. The barrier to creative debates

The traditional world of learning uses the language of the conceptual system of modernity. In debates on elearning many conflicts are caused by the debating parties using different conceptual sets, and because of this the opportunity for understanding and a common approach are limited. For the same reason the preparation of governmental strategic plans is also made more difficult.

2nd Table: Various concepts of education/learning

|

Concepts of a closed, hierarchical educational environment – the conceptual system of the industrial society

|

The concepts of an open, cooperative educational environment – the conceptual system of the information society

|

|

Instructionist theory of learning

|

Constructionist theory of learning

|

|

Central curriculum (the “curriculum law”

|

Flexible competenceportfolios as learning objectives

|

|

Linear curriculum

|

Modular organisation

|

|

Textbook

|

Information background environment on the Net

|

|

Frontal classroom environment

|

Cooperative classroom environment

|

|

Lectures

|

Projectbased learning

|

|

Communicating knowledge “from above”

|

Collective search for knowledge, consultation in knowledge management, selforganised learning

|

|

Centralised distribution of information

|

Parallel processing of information

|

|

Teacher

|

Tutor, moderator, consultant, coach, network organiser

|

|

Learning

|

Collective knowledge management, hyperlearning

|

|

Definition knowledge

|

Information management, search, documentation, communication knowledge

|

|

Grades, marks

|

Individual, but collectively compiled competenceportfolios, knowledge maps

|

|

Examinations, state examinations, reports

|

Competenceportfolios jointly completed by the teacher and the student

|

|

Examinations period

|

Selfassessment, joint assessment of the route leading to a desired outcome

|

|

Uniform written tests for everybody

|

Freestyle essays, individually selected tests, creative project tasks

|

|

Degree

|

Formally and informally acquired competences in the eportfolio

|

[header=Bibliography]

Bibliography

Barabási, Albert László (2002): Linked. The New Science of Networks (Perseue, Cambridge, MA ,http://sohodojo.com/ribs/linkednetworks.html 08.01.2008, accessed: 8. January 2008)

Bessenyei, István (2008): Teaching and Learning in the Information Society (in: Róbert Pinter (ed): The Information Society. Gondolat – Új mandátum, Budapest)

Linde, Charlotte (2001): Narrative and social tacit knowledge (in: Journal of Knowledge Management, 5/2, pp. 160

171.,

83733, accessed: 8 January 2008)

Nyíri, Kristóf (1997): Open and Distance Learning in the Information Society (http://www.eurodl.org/materials/contrib/1997/eden97/nyiri.html, accessed: 8 January 2008)